By Matt Hendrickson, Marker | Inside the office on the second floor of music industry mogul Merck Mercuriadis’ off-white townhouse in the posh London neighborhood of Notting Hill, there is shit everywhere. Hundreds of vinyl records are piled in shelves, while others are stacked 20 deep on the floor. A Michell Engineering turntable worth more than $10,000 is still wrapped in plastic on a card table. There’s a mound of CDs teetering next to two signed copies of English rock singer Ian Hunter’s recent memoir, one of which will go to Morrissey, whom Mecuriadis managed for several years. An original 1969 pressing of the only album by the German group Organisation, a precursor to Kraftwerk, is finally on its way, after Mercuriadis — who also managed Elton John and Axl Rose in a former life — spent almost 40 years tracking it down. “I don’t believe in material things. I always wear black, and I don’t have a car,” he says. “But I’ll gladly pay 400 quid for a record.”

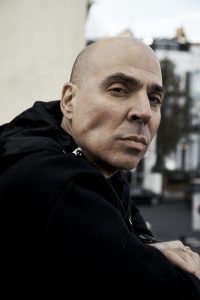

Which is why on this cool, late-fall day in mid-November, Mercuriadis is going record shopping — again. On his way to the seminal London record store Rough Trade, only a few short blocks from his house, with his bare head and stocky frame he could easily be mistaken for a Greek mobster. But today his mode is more tour guide as he spits out questions like quarters from a slot machine: “What’s your favorite band?” “Do you have a holy grail of a record?” Across the street, in the gray townhouse, he tells me, is where Brian Eno lives. There’s the Globe, a Jamaican-inspired dance club that the Clash loved. The Tabernacle, a venue where Pink Floyd — Mercuriadis’ all-time favorite band — used to play.

He walks into Rough Trade and ducks behind the counter. “Merck and Elton are our best customers,” says Sean, the store’s buyer. Now down to business: the records.

“There’s a Fontaines DC 12-inch,” Sean says.

“I need that,” Mercuriadis replies.

“A Madonna remix 12-inch?”

“I need that.”

“Cate Le Bon?” Mercuriadis looks at Sean incredulous.

“Do I look like I want a Cate Le Bon record?” Sean chortles.

A clerk tallies up the 25-odd albums. As he waits, Mercuriadis thumbs through another stack of vinyl, stopping to look at the cover of Taylor Swift’s latest, Lover.

“Should I add that too, Merck?” Sean asks with a sly grin.

“No,” Mercuriadis answers. “I already own 10 songs on it.”

Music royalties are the ultimate intellectual property (IP) game. Depending on who owns the copyright to a song, be it the composer, publisher, recording artist, or anyone else who may have been involved, they get paid every time someone wants to use their IP. Though valuations of the major labels are currently at an all-time high — they generated $14 billion in 2019 alone — between iTunes and Spotify, the past 20 years have been volatile for them. Royalties, however, have been the one constant, viewed as the safe long-term play: No songs, no hits, no money. Now private equity firms, institutional investors, and high-profile managers want in on it, too. In recent years, billions of dollars have flooded the music business to invest in the catalogs of songwriters.

> > > > > > > > >

Long story but worth the read, especially for songwriters!

https://marker.medium.com/the-man-whos-spending-1-billion-to-own-every-pop-song-75df0024155b