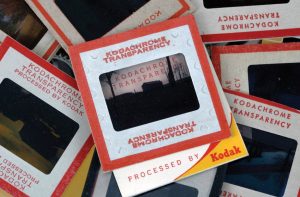

In this Sept. 4, 2008 file photo, Old Kodachrome slides are seen in Clarence, N.Y. The Eastman Kodak Co. is retiring its most senior film after 74 years in the company’s portfolio because of declining customer demand in an increasingly digital age. (AP Photo/David Duprey, File)

Film photography faded so swiftly that some days it can be hard to recall a time before digital photos.

Just two decades ago Eastman Kodak was selling a billion rolls of film a year. Another giant of film was Polaroid — a name that still had enough cultural cache in 2003 that most people knew what hip-hop duo OutKast meant when they sang, “Shake it like a Polaroid picture.”

But Polaroid stopped making its instant cameras in 2007 and Eastman Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012.

Kodak was forced to stop production of many of its film brands — including in 2009 the iconic Kodachrome, the world’s first successful color film. The sister brand of Ektachrome had become a cultural touchstone, responsible for capturing many family moments in the country’s post-war boom. It inspired Paul Simon to implore in song, “Mama, don’t take my Kodachrome away.” But technology caught up with film. And in 2010, photographers with their last rolls of Kodachrome film made rushed pilgrimages to Parsons, Kansas, home to the world’s last processor of a once-ubiquitous film brand.

Ektachrome, which first hit store shelves in 1946, is known first as a slide film. It was celebrated for its rich, distinctive look — and for being particular about how it was exposed. Professional shooters, like those at National Geographic, swore by it.

“It really was the gold standard,” said T.J. Mooney, product business manager for “film capture” at Kodak Alaris, one of the companies that emerged from Eastman Kodak’s bankruptcy.

Then Ektachrome was killed off in 2012 — the last of Kodak’s chrome films, just another digital photography casualty.

On Wednesday, Kodak Alaris announced that it was reviving Ektachrome. The 35mm film will be available later this year.

The website Phoblographer called it “a super shocking announcement.”

Photographers — pros and amateurs — took to Twitter to express their joy, including,

“My timeline has been filled with so many happy likes and retweets of #KODAK #ektachrome joy”

The company made the announcement at CES — the annual tech fest that in many ways celebrates the very tools that killed off Ektachrome and Kodachrome and so many other films in the first place.

Ektachrome will join a handful of other Kodak films that still exist — Kodak Gold 200, Kodak Ultra Max 400 and a series of professional films, Mooney said.

Kodak Alaris has enjoyed moderate growth in sales of its professional films, Mooney said. There is a market. An off-shoot of Polaroid in recent years has re-emerged as a niche product. It seems that the digital revolution might not erase all that came before it.

But what about the fate of Kodachrome — the most famous and revered of the bunch?

The company thought about it.

“Kodachrome will not be coming back,” Mooney said. “We took a look at it and decided Ektachrome was the better choice.”

Part of the reasoning was technical. Kodachrome is notoriously difficult to process. Not just any film processor can do it. “You almost needed a PhD in chemistry,” Mooney said. That skill was lost when Kodachrome disappeared seven years ago.

And some things just can’t be replaced.

By Todd C. Frankel, The Washington Post

http://www.denverpost.com/2017/01/09/kodak-bringing-back-ektachrome-film/

[Thank you to Alex Teitz, http://www.femmusic.com, for contributing this article.]

[We added this article knowing that so many musicians are photographers – and that many photographers love taking photos of musicians!]