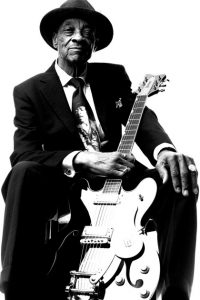

The next time you hear a debate on who should be inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame, be sure to bring up the name of Hubert Sumlin.

As pointed out in the new documentary “Sidemen: Long Road to Glory” (which opens Friday), the Delta blues guitarist isn’t a household name. But his dynamic playing is so revered that more than a dozen previous HOF inductees, including Eric Clapton, Elvis Costello, Keith Richards and Steve Winwood of Traffic, have petitioned the institution to induct Sumlin as one of the greats.

“They’ve all explained how important Hubert was to them,” director Scott Rosenbaum tells The Post about the man who played with both Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. “So many famous musicians owe Sumlin a debt. I think the Hall of Fame should give it some serious consideration, and I hope this movie helps Hubert’s case.”

Should it happen, Sumlin won’t experience the honor himself. In 2011, just months after being voted 43rd in Rolling Stone’s list of 100 Greatest Guitarists, Sumlin died in New Jersey at the age of 80. The Rolling Stones, who lifted directly from Wolf and Sumlin with their 1964 cover of “Little Red Rooster,” paid for his funeral expenses.

“Some white musicians get a lot of flak for co-opting the blues and not giving back,” says Rosenbaum. “But the Rolling Stones have always been supportive of the blues men. They always checked in on Hubert to see how he was doing, and if he needed any help.”

“Sidemen: The Long Road to Glory” also explores the story of Pinetop Perkins (who gave Ike Turner piano lessons) and Big Eyes Smith (who played piano and drums for Muddy Waters), and the role these often overlooked musicians played in altering the course of music history. But it’s Sumlin who has the most fascinating story.

When Sumlin was just a boy, growing up in the Mississippi Delta during the 1930s, his brother created a makeshift guitar by nailing a piece of bailing wire to the side of the family’s shack. A glass Coke bottle served as a slide.

Eventually, Sumlin grew up and moved to Chicago, where Wolf enlisted Sumlin to play in his band, providing the perfect accompaniment to his distinctive vocals.

Even among his peers in the Chicago blues community during the 1950s, Sumlin was respected.

“Muddy and Wolf were rivals, and one time [in 1956] Muddy sent his driver to Sumlin, and gave him $300 in $1 dollar bills to join his band,” says Rosenbaum, who spent five years piecing the film together. But after a hard stint of touring, in which he doubled as Muddy’s driver, Sumlin returned to Wolf, whom he regarded as a fatherly figure.

“Wolf and Hubert are a package deal,” says Rosenbaum. “You can’t separate the two.”

By Hardeep Phull

http://nypost.com/2017/08/17/the-rolling-stones-want-this-guy-in-the-rock-roll-hall-of-fame/