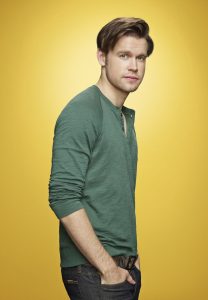

GLEE: Chord Overstreet as Sam on the sixth and final season of GLEE premiering with a special two-hour event Friday, Jan. 9 (8:00-10:00 PM ET/PT) on FOX. ©2014 Fox Broadcasting Co. CR: Tommy Garcia/FOX

Chord Overstreet comes from a prominent musical background with his father Paul Overstreet being a renowned country singer/songwriter. Ever since the end of Glee, Chord has been busy trying to carve a career for himself in music, starting with his first single ‘Homeland’, which has garnered quite a following. Chord has been on the road across the country to promote his new single and connect with his fans. After performing at the Rockwood Music Hall in New York, I got to speak with him after the show on the inspiration behind his new song, his influences, and what’s coming next for him.

Thanks for taking the time talk with me. Can you tell me a bit about your new single “Homeland”?

I was going to a lot of sessions every day and working with other producers, kind of doing the whole speed-dating thing that is writing songs. I had a title idea in my phone that was just not really hitting and I didn’t know what to write and I kind of let them work on the music of it and I kind of had this idea. In 15 minutes, I had all the lyrics for “Homeland” written out like that. It just kind of fell out of the sky and into my lap, and I was really homesick and I was thinking about where I learned to drive. My dad had this old truck that he kind of took on these back rows and kind of showed me how to drive when I was nine or ten, and I just was thinking about that. Every time I go back for the holidays, that truck is always sitting in the backyard just like broken down and haven’t moved since then. Everything about that town kind of still faded and almost as if it hasn’t changed since I was like a kid. I thought that was an interesting kind of thing that I really missed that time of my life so I started writing this song and it kind of happened really quick.

I’m glad you mentioned that because you did say on stage that you grew up in Nashville. Has growing up there influenced your music?

I would say growing up in Nashville has been a huge influence in my music. Growing up with my dad being a Grammy-winning songwriter of the year for five consecutive years in a row and having that legacy he has had has been a huge influence. I got to write a lot with him growing up and he kind of showed me the ropes. I always wanted to be like my dad, so I feel like that was the biggest influence and my mom was driving me back and forth to guitar lessons growing up and was super supportive and probably my biggest cheerleader. Both of them combined was the best parents, so I think a combination of seeing my dad be successful at writing music and being very critically acclaimed gave me a lot of drive to get there and thinking it’s possible versus not knowing what the hell I’m doing and I kind of had a lot of good influences around me, but Nashville definitely played a huge part of that. My stuff’s not country, but it’s storytelling, which I think is the root of country music so I think you can incorporate that. I think people want to hear stories.

Definitely. Now I know that you are coming off of Glee, which ended a few years ago. Looking back, how has that helped shape you in your career as a musician?

It was interesting because it was kind of like college for me in a sense of I was very raw and kind of dawn. I say that one of the things that helped me was jumping in to performing in front of a lot of people and being comfortable getting a stage presence knowing what I’m doing. It’s one of those things where I got thrown into the heat of it all being very green and it really helped me become more comfortable and more ready to go on the journey of my own. As far as performing goes, you can’t get that experience anywhere else not knowing what you’re doing. But, it was one of those things where you look back on now and it feels like a completely different life. I watched some of the stuff and I can’t even believe that ever happened, it feels like so long ago but it was only two years ago.

Were there any singers or musicians that you looked up to for inspiration?

One of my favorite singer-songwriters is James Taylor and my dad was obviously the main influence. I think David Gray is great. Four of my favorite bands is Aerosmith. I like all that singer-songwriter stuff. Jimmy Buffett, like the storytelling aspect and kind of what he does. I’m very focused on lyrics when I’m listening to music and I gravitate towards that. I’m kind of a geek when it comes to older music, like the 70s kind of stuff like Paul Simon, Hall & Oats…Bob Dylan. That’s the stuff that lives on forty plus years.

What kind of stuff can we expect from your own music? Is a new album in the works?

It’s a lot of history that I’ve been through. Everybody can’t relate to exact stories, but I feel like with everybody, the emotion behind the story is kind of what people can latch onto. Regardless of what your scenario is, everybody’s been through that emotion and if you can portray that and communicate that with an audience, I feel like they can relate to it. I’m probably going to do an EP before the album with like five songs. I feel like their just different experiences I’ve been through in life and kind of growing and learning. I hope people like it, but I’m just starting off with an EP and just get a little bit out there.

Are you still working on the EP at this time?

I think all the songs have probably been written. I probably have like a hundred different songs and I’ll probably have ten songs out of that or I think that are up to par. Probably do an EP of like five songs and then see where that goes and then drop an album a little bit after. I think the plan is to kind of introduce myself to people and know who I am versus the character I play and just kind of have people get to know me before we drop a full album, so people are a little more engaged.

So what is next for you? I know that you are still touring, so will you be working in the studio anytime soon?

Any chance I get to go in the studio when I’m home or back in town, I’m going to get to write as much as possible. But on the other hand, I also want to play as many live shows as I can because you can’t get that feeling anywhere else. So, I think I’m going to try to get as much live stuff out of myself as possible, and then whenever I get a day or two to kind of create some stuff, I’m think I’m just going to try to get some sessions in.

Are there any musicians past and present that you would want to collaborate with?

I would love to do a song on stage or a recording with James Taylor. That would be like the coolest thing ever, I mean he is like probably the all-time singer-songwriter. Obviously getting Paul McCartney would be pretty dope too. I kind want to be part of great music.

Great. So before I end our chat, let me ask you this. What would be your ultimate cover song you would like to perform?

I love singing ‘I Can’t Make You Love Me’ on the radio, which was written by one of my dad’s good friends Allen Shamblin. It’s been one of my favorite songs; you can play it with a guitar and just evoke what it sounds as good as it is for the whole band. It’s one of those really powerful songs that I feel like everybody can connect to. It’s one of my favorite covers.

Awesome. Well, I can’t wait to hear the rest of your music when it comes out and good luck with the tour.

Thank you very much.

Be sure to follow Chord Overstreet on these social media platforms:

https://www.facebook.com/chordoverstreet/

https://twitter.com/chordoverstreet

https://www.instagram.com/chordover/

By Mufsin Mahbub AOL BUILD Ambassador

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/57df74bbe4b0d5920b5b2fe8

* * * * *

Music Festivals and the Pursuit of Exclusivity

Promoters, venues, and talent buyers on how radius clauses really work

It’s been a long three months, but summer has ended, and the frenetic festival machine unique to the season has finally come to a rest. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that musicians, fresh off those massive summer stages, will kick back and relax. In a music industry where touring has become an increasingly important source of income, it’s not at all surprising for bands to hit the festival circuit, take a breather, then go at it all over again.

It makes sense — after all, the onset of fall and its attendant tour cycle is an opportunity for musicians to take advantage of the exposure they’ve gained at festivals. But those tours don’t come easy. Agents and artists must take particular care to navigate around the various festival radius clauses that are out there.

Radius clauses are clauses in live music performance contracts that stipulate that an artist won’t play shows within a certain radius of said performance for a period of time, so the show being booked won’t be undercut by competing gigs. They’ve long been standard industry practice, but in North America’s viciously competitive festival landscape, sprawling radiuses by leading festivals have become markedly controversial, spawning debate about the creation of monopolies and the race for exclusivity in the live music industry.

Just take Lollapalooza, whose expansive radius clause is among the most maligned in recent history. (The festival declined to comment for this story.) Much reporting on the 25-year-old festival’s use of radius clauses has seized on the upper ceiling: 300 miles around Chicago, six months before the festival and three months after. “Lollapalooza’s embargo — anywhere from 90 to 270 days and 90 to 300 miles — is theoretically broad enough to keep Chicago up-and-comer Chance the Rapper from performing in his hometown for nine months this year. It’s bad for the artists and for the fans,” Mic noted in 2014, arguing that while superstars can have their radiuses waived, “mid-level” artists suffer the strictures of the clause.

But this fall, 2016 Lolla acts of varying tiers are hitting the road. Artists like Frank Turner, FIDLAR, Mac Miller, Danny Brown, and Die Antwoord are making stops in cities squarely within the 300-mile radius or even returning to Chicago. So how exactly are their radius clauses enforced? How well do we consumers outside the industry really understand radius clauses and how they work?

With Lollapalooza as a focus, Consequence of Sound spoke to festival organisers, talent buyers at concert venues, and booking agents who work within 300 miles of Chicago to find out just how radius clauses work and affect smaller promoters and venues and how the pursuit of exclusivity will change in the festival landscape’s uncertain future.

What became obvious very quickly in this deep dive into radius clauses is that there’s no one size fits all. A radius clause is “something that is scalable to whatever artist it’s applying to,” says Pete Anderson, an agent in the concerts department at APA who covers the west coast. Speaking from the hypothetical point-of-view of a Coachella-tier festival, Anderson explains: “If you’ve got a developing artist, like The Preatures from Australia, for example, then you’re not going to be worried if they play a show in Boise, Idaho.

“But if you have an artist that’s legendary in scope, like David Gilmour, who plays very few shows a year, then you’re gonna want to protect your interests a lot more, because you’ve got a lot more money at stake.”

This is intuitive. There’s no way the contracts Pinegrove and Radiohead signed for their performances at Lollapalooza this year were identical. But what might be trickier to digest is how a radius clause is simultaneously a contractual condition to be adhered to and also something that is almost always negotiable.

“I slap a huge radius on all of my offers,” says Seth Fein, founder of The Pygmalion Festival in Urbana-Champaign, IL, a few hours’ drive south from Chicago. “But I always tag it with the same thing: ‘negotiable.’ It’s in caps.

“When I put in an offer, I want the agent to know right away that, ‘Hey, we’re having a discussion. I’m offering this amount of money and these amenities. I expect this amount of radius, but let’s talk. Let’s be human about this and try to come up with a solution that makes the most sense for both festival and artist.’”

That task of negotiating a radius clause falls to booking agents, for whom “everything is a conversation,” says John Chavez, vice president of Ground Control Touring, who’s booked tours most recently for Real Estate, DIIV, Deer Tick, and Wild Nothing.

“It’s always a conversation, and sometimes that conversation doesn’t go your way. But there’s never [a radius clause] that comes up and it’s a hard ‘No, we’re not looking into this,’ because it’s my job to look into it.”

Conversations between booking agents and festival talent buyers – that’s how we get tours and shows that appear impossible under the strictures of radius clauses. They are often announced under particular conditions: For instance, booking agents might only be allowed to announce those tour dates after the artist has played their festival gig or may be obligated to keep advertising to particular markets.

And so, just because a performance appears to clash with a festival’s radius clause doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a ‘violation,’ because it might very well have been negotiated into being. It’s widely accepted that headliners are the most constrained by radius clauses, but it’s still possible to wrangle headlining performances at two competing festivals within the same region, as OutKast proved in 2014 at Lollapalooza and Summerfest in Milwaukee, WI.

“The only time you’d ever break a radius clause is if it’s discussed with the promoter in advance and they know what you’re doing,” says Chavez. “So in that sense, they’re always abided by. Because if you break a radius clause [without telling the promoter], then you don’t have any power to re-negotiate and fix it. If you break a radius clause, then the promoter is completely within their rights to kick you off the fest or duck your pay.”

How do promoters decide whether an artist can play another show in their radius? For React Presents, the Chicago company behind North Coast Festival, Mamby on the Beach, and Spring Awakening, it boils down to factors like “the nature of the relationship, the proximity and size of the show that’s in our radius, as well as the perceived effect that it will have on our show’s bottom line,” co-founder and partner Lucas King said over email. “The general rule is ‘If you’re fair to us, we’ll be fair to you,’ to a certain extent, but we also have to protect our investments.”

Those investments, which can run up to millions of dollars for legends and headliners, are not taken lightly in today’s uncertain festival landscape. And as multiple interview subjects pointed out, radius clauses are necessary to protect those investments, whether it’s by pre-empting problems by starting negotiations or by initiating attempts to recoup lost profits. “Festivals have the right to protect their business interests,” says Anderson. “Talent bookers who are adversely affected can criticize, but it’s the world we live in.”

But in trying to protect their investments, do festivals overreach? Radius clauses are negotiable, but do festivals end up monopolising talent at the expense of smaller venues and promoters?

In 2010, Lollapalooza came under investigation by the Illinois Attorney General for anti-trust issues pertaining to their radius clauses. Although that investigation apparently went nowhere, it reportedly stemmed from local promoters and venues’ complaints that Lollapalooza was creating a dearth of bookable talent during the season.

“[Lollapalooza] sucks up all our talent during the summer,” Nick Miller of JAM Productions told Chicago Tribune music critic Greg Kot in 2008. “During the summers now, you’re lucky if you have a couple of shows, and you’re just picking up the leftovers that couldn’t get into any of the festivals,” Sean Duffy, talent buyer at The Abbey Pub, told WBEZ critic Jim DeRogatis. “And some bands that play at these festivals can’t play anywhere else in the city for 90 days before and 90 days after – that’s six months, and that’s just ridiculous!”

In 2016, the city’s festival scene is different. Lollapalooza, now a Live Nation-owned, four-day extravaganza that can be counted on to sell out annually, is bigger than ever. Other landmark Chicago festivals like Pitchfork Music Festival (which began in 2006) and Riot Fest (which began in 2005) have come into their own. And the passing of time has helped normalize the coexistence of festivals and venues in Chicago, not to mention their collaboration in the form of after-shows and after-parties.

It’s “reality” that the numerous festivals in Chicago – and the hundreds of bands that play them – will translate into some lost plays for Chicago clubs, says Bruce Finkelman, who owns The Empty Bottle and Thalia Hall. “We do what we need to do to present the best music we can. There’s no use crying over spilt milk; it is what it is.”

“I think festival promoters and venues nationwide – not necessarily just in Chicago – have come up with ways to work together that benefit everybody a bit more than they used to,” says Patrick Van Wagoner, talent buyer and director of music operations at Schubas Tavern and Lincoln Hall. He and fellow talent buyer Dan Apodaca haven’t observed any lack of talent available for booking, particularly with the smaller capacity rooms of Schubas Tavern and Lincoln Hall, which give them a wider range of artists to book. “We definitely still book shows year round and book shows that we’re proud to have.”

Lollapalooza’s radius, with its upper ceiling of 300 miles, theoretically covers a huge territory, a point of criticism. But non-Chicago talent buyers and promoters within that radius often said it doesn’t affect them as much as some might think, though that doesn’t mean they can disregard it, or radius clauses in general.

“For us, we’re two hours away and in a different market, so it’s less of an issue,” said Seth Fein of Pygmalion Festival. “They’ve never blocked us from anything that we wanted to share … I’ve never had to get on the phone or have a meeting with C3 about it.”

“It’s no secret that there are a lot of bands that we would love to have come play Indianapolis, but can’t,” said Josh Baker, co-founder of independent promoter MOKB Presents and co-owner of The Hi-Fi. “Especially in the summertime, with Forecastle, Bunbury, Lolla – but Lolla not so much.”

For all the scrutiny Lollapalooza’s radius clauses are subject to, it’s hardly the only festival talent buyers and venue promoters have to keep in mind when planning their calendars. The myriad of music festivals that coexist in a single region can create a “venn diagram” with their different radius clauses, as Billy Hardison, one of the co-founders of Production Simple in Louisville, KY, put it.

Although summer is traditionally a slower season for club shows, with these overlapping radius clauses, “it can get quiet in Louisville. We can struggle to fill our calendar,” he says. “And for dates outside the radius, like in March and October, we get hammered. It gets even busier. There used to be maybe 20 shows in October. Now there could be 30.”

“If every fest disappeared, my calendar of shows would be more spread out, and I would be making more money. But that’s if wishes were horses,” says Hardison. “I’ll take what I can get.”

The talent buyers and venue promoters interviewed for this story rarely responded to questions about expansive radius clauses with indignation or outrage (often because they make use of radius clauses themselves). Rather, they were realistic: Some artists are going to slip through their fingers, and that’s a fact of the business.

“Ultimately, that’s okay,” says Fein. “It’s not like it’s ever, ‘Holy shit, there are no artists.’ There are always artists. You just have to be a good buyer and a smart buyer.”

“It just forces others to be a little bit more creative in that time frame,” agreed Baker of MOKB Presents. “If you know you’re going to lose 25 or 30 acts, you’d better get your ass in gear and find some more to fill the dates.”

It can be frustrating when an act you’ve been working to secure for some time is suddenly off the table because they’ve been booked by a festival, says Baker. But some losses sting less than others, and sometimes they don’t sting much at all, because some artists were never suited to your stage to begin with. As Jason Huvaere, the founder of Paxahau Events, which runs Movement Festival in Detroit, MI, explains, it’s not really sensible to blame a nearby festival for keeping a rock or EDM show with multimillion-dollar production out of your local nightclub.

“But with some artists, like a smaller DJ, it can become unrealistic,” he says. “Because there’s a DJ that’s performing up on a stage at a festival; then you tell the entire nightlife community in that town that they’re not allowed to see that DJ for six months because if they wanna see him, they have to go to the festival – that gets a little tough. That gets a little sticky.”

Artists and agents who consent to the parameters of exclusivity outlined in radius clauses know that means being walled off from other festivals and venues. As Fein points out, it’s a strategic financial decision at hand – after all, the more exclusive and more desirable the performance, the higher likelihood of a big paycheck.

“Vince Staples isn’t going to hit Champaign-Urbana on a routed tour unless Vince Staples is going to get money: the kind of money that he’s going to be able to get in a major market. It’s not worth it [otherwise],” he says.

This year, Pygmalion Festival has scored Wolf Parade and Future Islands, two headliners who will play their only shows in Illinois and most surrounding states this year (though both acts will also be hopping over to Midpoint Festival in Cincinnati).

“I think these were strategic moves by their management more than giving Champaign and Pygmalion the exclusive in the radius,” says Fein. The questions at hand were: “What is the value of a festival play in Champaign if there’s no Chicago play? Versus, what is the value of a festival play if there is a Chicago play, or a Bloomington, Indiana, play, or an Iowa City play?”

It was hard to write this story without being aware that there were likely many other shades to the issue – uglier, more political spats over radius clauses that would scarcely be disclosed on record – even as most of the talent buyers and promoters interviewed for this story spoke of cordial and collaborative business relationships with big festivals.

“It’s not about some festival nefariously trying to put small clubs out of business. It’s about protecting their own interests,” says booking agent Pete Anderson.

As it stands, MOKB Presents in Indy only loses a handful of bands each year to festivals with radius clauses, says co-founder Josh Baker. If another festival pops up, though, “it could be problematic. But it’s not usually anyone’s fault. I mean, any good agent worth his salt – and most of the ones we work with are – is not going to deliberately try and screw over a promoter.”

Interpersonal industry ethics aside, festivals are still part of the wider live-music ecosystem and have to inevitably “play ball” with everyone else, Baker says. “Festivals, they’re a once-a-year thing. Promoters, radio stations, and record stores are out here operating every day of the week.”

“There’s only so many dates and only so many markets. Touring is very expensive,” Anderson points out. “Festivals know that, and if they’re not paying a fee that makes sense for [an artist] to play that festival as a one-off, that artist has to tour there. So festivals do have an interest in working with surrounding clubs.”

That said, the Illinois Attorney General found enough reason to open an investigation into Lollapalooza and the festival’s use of radius clauses. Competition between festivals in North America has heated up in recent years, and the booking agents interviewed for this story have found some radius clauses enforced more strictly in this environment. “I’ve seen festivals disallow radio shows in certain radiuses. I’ve seen promoters that limit the number of festivals you can do in a hemisphere of the country,” says Anderson of festivals’ “ever-evolving” business interests.

And now that the festival bubble has all but burst – a situation Stereogum has so succinctly and decisively articulated here – even greater protections might be on the horizon, though it’s anyone’s guess. As React Presents co-founder Lucas King put it, “Radiuses are more important than ever before … Making a festival experience unique, including who is on the lineup, is more important than ever – and we don’t just say that philosophically, meaning it is important for survival.”

By Karen Gwee

http://consequenceofsound.net/2016/09/music-festivals-and-the-pursuit-of-exclusivity/

[Thank you to Alex Teitz, http://www.femmusic.com, for contributing this article.]* * * * *

Fans Still Prefer Music Live to Digital, Nielsen Music 360 Report Finds

Fans await the arrival of DJ Calvin Harris in April at the 2016 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in Indio. A Nielsen Music survey has found that consumers spend more money on live music events than any other way of experiencing music. (Katie Falkenberg/For The Times)

Randy Lewis

How do people most like to enjoy their music? Live, at least according to the Nielsen Music firm’s latest edition of its Music 360 report, which tracks how consumers take in music in today’s fractured, multi-platform world.

Of all the ways to experience music, Nielsen found, 36% of consumers’ money spent goes toward live events, far and away the most popular way of consuming music.

Of course, that no doubt partly reflects the fact that the cost of tickets for most live events far outpaces the cost of buying downloads, CDs or paying for a monthly streaming subscription.

But in an intriguing facet of the study into the changing habits of fans in an era in which music is increasingly defined by streaming services, 21% of overall music spending still goes toward physical CDs or downloaded digital singles and albums, compared to only 6% to streaming service subscriptions.

Among 13- to 17-year-old consumers, 38% of their money is spent on physical and digital albums and tracks, with a higher-than-average 9% for streaming services, and just 5% for satellite radio subscriptions.

Those are just a couple of highlights of the report, which Nielsen has excerpted for public consumption from the full paid study that goes out this week to its entertainment industry subscribers.

“Fans are interacting with music differently,” the report’s summary states, “but their passion for music remains strong. In fact, listeners are spending more time and more money on music-related expenses in 2016 than they did in 2015.”

On the streaming front, Nielsen reports that 80% of music listeners used such a service during the 12 months preceding the study. The report was conducted from July 14 to Aug. 5 of this year, among 3,554 consumers “reflective of the population of the United States.”

That figure is up five percentage points from a year earlier, when 75% of respondents said they had used a streaming service in the prior year.

In terms of the time spent listening to music, Nielsen reports that radio is still the most popular method, accounting for 27% of the time people spend listening by format. Digital music collections accounted for an additional 20%, followed by streaming of on-demand audio (12%), programmed audio (11%), and music video and physical music collections (tied at 10% each).

Demographically, Hispanic consumers (as defined by Nielsen) spent on average 90% more on music than the general population and also scored higher numbers than average for attending DJ events and smaller live music sessions.

Hispanics also posted higher numbers than teens or millennials (ages 18 to 34) for attending live concerts with one main headliner, small live music sessions, live concerts with multiple headliners, music festivals, club events with DJs and club events with a specific DJ.

The survey also explored music preferences broken down by political affiliation, with Democrats scoring higher than the general population in money spent on club events with DJs (124% more than average), small live music sessions (+54%), digital music (+43%) and video on demand or pay-per-view services (+38%).

Republicans, meanwhile, spent more on premium TV subscriptions (76% above the general population), comedy performances (+65%), sports events (+35%) and satellite radio services (+32%).

Entertainment options that appeal the most to independent voters were video games (+42%), live music concerts (+31%) and paid online streaming (+14%).

The study also digs extensively into how consumers respond to branding affiliations at concerts and festivals they attend, with nearly two-thirds of festivalgoers saying they viewed a brand more favorably if they offered product giveaways at live events and nearly as many (64.8%) saying the same if a brand sponsors an air-conditioned tent at a festival.

More than half (53.7%) said their estimation of a brand improves when that brand sponsors an existing festival, while 46.3% said they view the brand more favorably for producing its own music festival.

By Randy Lewis

randy.lewis@latimes.com

Follow @RandyLewis2 on Twitter.com

Copyright © 2016, Los Angeles Times

[Thank you to Alex Teitz, http://www.femmusic.com, for contributing this article.]